Verdict: Here is a book that deserves all of its accolades and its foundational status.

I’ve hit a point with my TBR reading (seriously, y’all should see these piles, they are ridiculous) where I’ve picked off the low-hanging fruit (the quite-short nonfiction like Janet Malcolm’s Psychoanalysis and Anne Fadiman’s At Large and at Small) and now there’s a lot of enormous books left, and particularly enormous nonfiction books. And since I have had a rough month, I decided to treat myself by reading the (presumed) loveliest of my nonfiction books first.

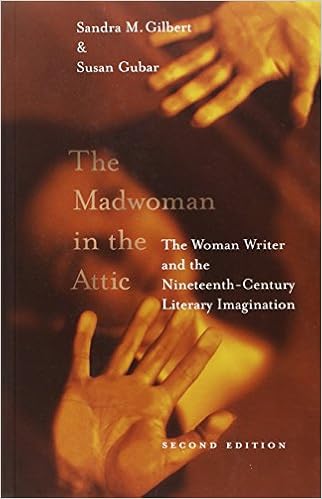

And indeed, I chose well! The Madwoman in the Attic is excellent for a nostalgic feminist English major like me. I love reading all about image clusters in Jane Austen (not sarcasm, I really love that). Definitely the book is a little dated, and definitely Gilbert and Gubar can be a little dogmatic about relating everything back to their Central Thesis, but overall, there is some damn good scholarship going on here. I thought I was so clever talking about how Shirley Jackson’s books all involve houses and their constrictions, but if I’d been really clever I would have pointed out that she belongs solidly in the literary tradition noted by Gilbert and Gubar.

Oh well. I will be that clever next time I have a conversation with someone about recurring imagery in Shirley Jackson novels. Because that’s a thing that’s likely to happen soon.

The first chapter discusses ideas of creativity throughout Western history and how the imagery of creativity comes up all dicks, and this I simply cannot understand. Like, obviously if you’re making the book/baby comparison, it’s going to be a little strained because you need to have one each of a man and a woman to make that happen. But I don’t understand how you could look at the contribution dudes make to creating babies (sperm) and the contribution women make (actually producing a whole entire new person from inside their bodies) and conclude that dudes are the ones with all the generative power. This seems totally crazy. That’s like saying John Watson is the crucial member of the partnership because he sometimes says something that plants the seed for a major Sherlock Holmes breakthrough.

(I don’t mean that I think dudes are John Watson and ladies are Sherlock Holmes in the baby-making endeavor. I just mean that a person living in the olden days, witnessing the things they were witnessing where [sex => lady grows large => entire brand new person comes out of her body], might reasonably see it that way, if they weren’t all messed up by societal investment in keeping women boxed in.)

The Jane Austen chapters are really solid. I both understand why Austen contemporaries criticized her — if you dreamed of freedom in a very unfree century, the way Charlotte Bronte and Elizabeth Barrett Browning both did, it is understandable that you would be less than thrilled about books that seemed to prop up a rotten system — and really love the feminist reading of her novels. Gilbert and Gubar keep on quoting this, my favorite bit of Persuasion:

“I could bring you fifty quotations in a moment on my side the argument, and I do not think I ever opened a book in my life which had not something to say upon woman’s inconstancy. Songs and proverbs, all talk of woman’s fickleness. But perhaps you will say, these were all written by men.”

[Anne said:] “Perhaps I shall. Yes, yes, if you please, no reference to examples in books. Men have had every advantage of us in telling their own story. Education has been theirs in so much higher a degree; the pen has been in their hands. I will not allow books to prove anything.”

Woohoo. Go Jane Austen. Still not as cool as Jane Eyre‘s line about “I am no bird, and no net ensnares me,” but pretty cool.

The Bronte chapters were also fascinating and cool to read. I mentioned in my review of The Woman Upstairs (a book that acknowledges its debt to The Madwoman in the Attic so often it’s like a tic) that I love Jane Eyre’s anger and unflinchingness more than anything else about her, and that quality of Jane’s is taken up and explored in great detail. Gilbert and Gubar basically talk about everything I love about this book, from Jane’s unflinching morality, to her anger, to Mr. Rochester’s attraction to her being based on her unwillingness to act in a subservient way.

There was some stuff about George Eliot too that meh, I don’t care about George Eliot SORRY GEORGE ELIOT YOUR BOOKS BORE ME, and although I do truly love Emily Dickinson I do not love seeing her poems explicated. The talk of “Goblin Market” was again excellent because that poem is damn creepy, and Gilbert and Gubar have this to say about Aurora Leigh:

It certainly deserves some comment, not only because (as Virginia Woolf reports having discovered to her delight) it is so much better than most of its nonreaders realize, but also because it embodies what may well have been the most reasonable compromise between assertion and submission that a sane and worldly woman poet could achieve in the nineteenth century. [emphasis mine because that’s the part that is true facts]

True, true facts, my friends. If you have not read Aurora Leigh yet, I strongly recommend you get right on it. God damn it is good. It is just so extraordinarily well-observed. You know how very occasionally you come across a line of poetry that describes something perfectly and perfectly succinctly? That is a phenomenon that happens over and over again in Aurora Leigh. It should be required reading in school. I’d be willing to sacrifice Tennyson for Aurora Leigh.

OH MY GOD and they also said this, which is possibly my favorite thing in the whole book:

Many critics have suggested that Dickinson’s reclusiveness was good for her because good for her poetry…Considering how brilliantly she wrote under extraordinarily constraining circumstances, we might more properly wonder what she would have done if she had had Whitman’s freedom and “masculine” self-assurance, just as we might reasonably wonder what kind of verse Rossetti would have written if she had not defined her own artistic pride as wicked “vanity.”

I want to give this passage a standing ovation. I get so tired of people suggesting that it was somehow “better” for artists to have suffered horribly because otherwise they wouldn’t have done art. I don’t buy it. I buy the above argument instead. I buy it in relation to advances in feminism and I buy it in relation to advances in mental health. So there.