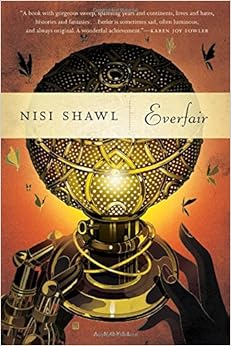

Note: I received an e-galley of Everfair from the publisher for review consideration.

The genesis of Nisi Shawl’s debut novel Everfair was the author’s bafflement that she had never gotten into steampunk, and her theory that the reason for this is steampunk’s uncomfortable connections with colonialism. Everfair, therefore, creates an alternate version of Congolese history in which white and black Europeans and Americans purchase land in the Congo to create a small country called Everfair. The residents of Everfair develop steam technology that allows them, in alliance with the indigenous king of the Everfair territory, to chase out King Leopold’s forces. Everfair follows the creation and development of this country over the course of thirty years.

Oh gosh. Ohhhhhh gosh. Please hold while I lie on the floor and catch my breath over the greatness of this book. Oh, where to begin. How shall I count the ways in which Everfair won my heart? I looooooved this book. It’s wonderful on its own merits, and it also made me feel excited for the ever-expanding (I hope) globalism of contemporary fantasy.1 Shawl writes from multiple viewpoints in a way that extends compassion to every character, but gives nobody a pass on their blind spots. The project of nation-building inevitably includes casualties, and Shawl never shies away from that truth, even when her characters do.

(Did you read The Just City? Did you like The Just City? This is kind of like that! But with more dirigibles, and in nineteenth-century Congo.)

If I had a complaint with Everfair, it’s that I wasn’t entirely ready for the way it makes large jumps in time and place. The chapters are short, which at first made it challenging for me to settle in comfortably to the point of view and time period of each one, and successive chapters are frequently set months ahead of the chapters that came before. This is doable — you have to pay attention to the chapter headings that let you know where and when the action is happening — but it was a little difficult for me to adjust to, right at first. It also gives rise to the kind of situation where one chapter will see the characters debating a heavily contentious issue of serious strategic significance, and the next will find you six months on, with that whole problem resolved and in the past.

However, Nisi Shawl is careful to catch you up to what’s happening, in ways that almost never feel like visits from the exposition fairy, and the benefit of this type of writing is that we truly get to see the growth and changes in Everfair over a course of decades. At first, there’s a degree of unity among the residents of Everfair: The most important thing for African, East Asian, European, and American Everfairians2 alike is to save as many people from King Leopold’s brutal rubber trade as possible, and ultimately to drive the Belgians out of the Congo.

But what truly made my heart sing3 was the second half, in which the priorities, loyalties, and demands of the different groups of stakeholders begin to conflict with each other. Shawl is respectful of everyone, laying out as fairly as possible the feelings and claims of the indigenous people of Everfair and its colonizers. She doesn’t try to find silver bullets for the problems in the world she’s created: Yes, the settlers were vital to driving out the Belgians; and yes, they shed blood and made their homes in Everfair; and still, the land belongs first and primarily not to Daisy Albin of England or Martha Hunter of America, but to King Mwenda and his people.

With all of this, Shawl brings her book to a conclusion that might be argued to be slightly too neat. When, after all, did competing land claims ever settle themselves bloodlessly? But there’s something revolutionary about a story of African colonialism in which opposing interests are able to find a peaceful middle ground.

I’ve been crazy psyched about this book — which really seems to cater to 100% of my interests — since December of last year, and it did not disappoint. Everfair! Read it and come back and squee with me!