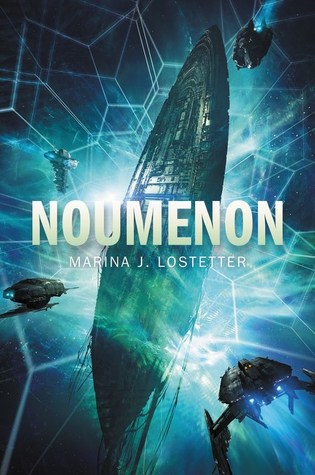

After telling everyone that I was hype as fuck for Marina J. Lostetter’s debut SFF novel Noumenon, I now can’t remember where I heard about it. If you’ve read and loved this novel, drop me a note in the comments and clear up my confusion. I’d probably have given up at the start if I hadn’t heard so much good about it; but then, of course, I wouldn’t be writing hundreds of words about the ways it wasn’t successful.

Noumenon is the story of a generation ship (well, a convoy of generation ships) setting out to explore an anomalous star called LQ Pyxidis. The journey will take hundreds of years and will be staffed by a series of clones whose originals have been heavily screened for any physical or mental problems that would cause problems for the convoy. The book consists of snapshots of the journey out to LQ Pyxidis and back to Earth, jumping ahead in each chapter by several decades and following a few key genetic lines through the convoy’s journey.

To start with the good, I love a generation ship. Generation ships are the closest thing SFF has to boarding schools.1 Lostetter does something I maybe haven’t seen before in giving us the entire journey of Convoy Seven (other convoys are launched from Earth at the same time to explore other parts of the galaxy), so that we see the mission through from its conception by Reggie Straifer, to its arrival at LQ Pyxidis, to its return to Earth.

Over the course of the clone generations, the convoy is perpetually trying to correct for the mistakes their predecessors have made. After a rash of suicides early in the mission, they begin to push hard on the notion of mission before individual, which in turn leads to its own set of problems. The decisions and emotions of individuals in any given generation have far-reaching consequences, and because Lostetter is dealing in decades and centuries rather than months and years, we’re able to see those consequences unfold. Noumenon is a book that’s keenly aware of the pitfalls of adhering too closely to the founders’ vision. It also knows that new generations, as they attempt to avoid the errors of their forebears, inevitably make shiny new mistakes. People don’t get smarter; we just get older. Only the convoy’s AI, I.C.C., is able to witness the full passage of generations and learn from each one as it goes by.

But for a book with such ambition in its premise and plot, Noumenon is surprisingly cautious with its characters and social ideas. Lostetter goes out of her way at one point to emphasize that biology isn’t destiny, but then makes a lot of choices in the book that suggest that it is. Unless I missed something, the straight characters’ clones are always straight (e.g., Reggie Straifer, Nika Marov), and the gay characters’ clones are always gay (e.g., Margarita Pavon). Nobody is ever trans. As a medium-sized spoiler for the seventh vignette (which frankly is given away by the title of the chapter), one child cloned from the genes of a computer specialist is raised believing that his original genes belonged to a plants guy. Despite this socialization, though, his heart always belongs to computers.

This was why Diego thought that if he were to reveal his secret — his distaste for botany — to anyone, it would be his mom. She was I.C.C.’s caretaker, and thought it would be nice if Diego shared her love of computers. And he did, so much so that he wished his genes had been brought on board for the AI. He wanted a job that wasn’t his, and he knew that was wrong.

None of the other clones — i.e., those who had the same jobs as their genetic originals — ever voices discontent with their task. For a book that repeatedly argues against holding clones responsible for the actions, choices, and tendencies of their genetic originals, Noumenon is strangely faithful to the assumption of biological determinism.

Lostetter also declines almost entirely to deal with race or nationality. In the first two chapters, characters are described in weird, racialized ways that disappear in later chapters — which charitably might be assumed to suggest that the narrators who grew up on earth are more conscious of race than the convoy characters. Either that or we’re just dealing with standard issue well-intentioned-white-lady writing awkwardly about race as we encounter characters for the first time.

With him was a dark-featured young woman, her hair as wavy and body as curvy as any Grecian goddess’s–Abigail, she’d said her name was.

and

Her eyes were a dark brown-and-gold under harshly cropped black bangs. Her expression carried the utmost seriousness, and her powerful, pointed movements were what Reggie might have expected from a strapping Russian man, not a petite Japanese woman.

and

Jamal was only perhaps half a foot taller than Reggie, but his lankiness gave the impression that he was a tower of a man. Neatly sheared dreadlocks were gathered in a ponytail at the base of his neck. He smiled broadly while they shook hands, and his smile shone bright white in his dark face.

Other characters are described as looking very Mongolian or very Polynesian. IT IS WEIRD AND UNCOMFORTABLE.

Nor does Noumenon posit any gendered, racial, or national awareness on the part of the convoy. Lostetter is clearly aware of and interested in dealing with the human tendency to prejudice: Eventually there emerges (spoilers here, again) a kind of slavery, which gets abolished, and then a kind of stigma against the former slaves. Lostetter thereby takes the path — incredibly common among SFF writers — of ignoring real-world prejudices in favor of invented ones (prejudice against certain genetic lines). And I just don’t believe it. I don’t believe that a convoy from Earth would retain no national allegiance at all, no awareness of different races, and no distinction among genders. Prejudices in real life are never instead of; they’re too. THAT IS KIND OF THE WHOLE CONCEPT OF INTERSECTIONALITY.

The Watsonian explanation for this, I think, is that the team organizing the convoy screened out — among other things — bigots.

The crew has been chosen based largely on their DNA and histories. On top of that, the consortium is getting full psych evals and family histories. There are predispositions that have been left out. Those with violent tendencies won’t be aboard, or those who lack loyalty, or those who are flighty. . . . No anarchists . . . . or dictators, or psychopaths, misogynists, etcetera. No matter how intellectually brilliant they are, without the proper emotional factors — emotional intelligence, if you will — they will hinder societal stability, and could endanger the mission’s success.

In past years I would have been more forgiving of this plot device: Lostetter doesn’t feel qualified to deal with race in her book (fair enough), so she handwaves it by implying that those people have been screened out. But one year into the Trump presidency, I am more than ever worried about propagating the narrative that prejudice is confined to an identifiable group of people. And since screening for rebels and authoritarians fails — we see clones who are both — it’s not reasonable to accept that screening for bigots worked flawlessly.

Again, Lostetter is clearly conflicted about genetic determinism and pushes back against it sometimes. The convoy decides to discontinue certain genetic lines if one of those clones behaves in ways they believe are detrimental to the mission (rebellion, suicide, etc.), and the book clearly believes this to be authoritarian folly. Yet when much or most of the clones’ makeup — from sexuality and gender to job preference — remains true to their genetic originals, it’s hard to feel that Lostetter doesn’t believe that at some level, biology is destiny.

tl;dr: Lostetter is full of cool ideas, but Noumenon disappointingly fails to grapple with the sociological implications of the world it sets up.

Have y’all read Noumenon? I’d be interested to hear other responses! Is my crabbiness just a function of having read and loved both Six Wakes (clones on a generation ship) and Ninefox Gambit (nothing in common with Noumenon really, but Yoon Ha Lee blurbed this book and the covers are sort of similar) this year? PS please read Ninefox Gambit because holy shit is it ever good.

- Just kidding. SFF totally has boarding schools. But still, generation ships are boarding-school-y, and I’m into it. ↩