The beginning: Hurrah, multiple points of view! (In retrospect, the multiple points of view is probably the reason I added this book to my TBR list in the first place.) Mudbound (affiliate links: Amazon, B&N, Book Depository) opens with two brothers, Jamie and Henry McAllan, hastening to dig a grave for their father before the rains start again; while Henry’s wife, Laura, barely conceals her relief at the old man’s death. Then we jump back in time a few years, to the time when Laura and Henry met and married and moved to Mississippi to run a farm there. Laura hates it, and hates even worse that she has to live with her sexist, racist, interfering father-in-law. We also get point-of-view chapters from Henry and Jamie, as well as various members of a black sharecropper family, the Jacksons, who work the McAllan farm.

Hillary Jordan is a gifted writer. The opening few chapters of Mudbound, which take place after the main action of the book, hint at what’s to come without drawing attention to the cleverness of the foreshadowing. This is a trick many authors struggle to accomplish. Jordan does it, I think, by not seeming to care what the reader knows or doesn’t know about the events of the book. Here’s an excerpt from Laura McAllan’s first point-of-view chapter:

But I must start at the beginning, if I can find it. Beginnings are elusive things. Just when you think you have hold of one, you look back and see another, earlier beginning, and an earlier one before that…

[M]y father-in-law was murdered because I was born plain rather than pretty. That’s one possible beginning. There are others: Because Henry saved Jamie from drowning in the Great Mississippi Flood of 1927. Because Pappy sold the land that should have been Henry’s. Because Jamie flew too many bombing missions in the war. Because a Negro named Ronsel Jackson shone too brightly. Because a man neglected his wife, and a father betrayed his son, and a mother exacted her revenge. I suppose the beginning depends on who’s telling the story. No doubt the others would start somewhere different, but they’d still wind up at the same place in the end.

That is a well-written and economical way of telling you, Expect tragedy. Okay, Hillary Jordan! I am duly primed for tragedy!

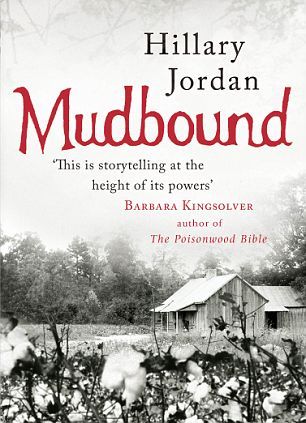

Cover report: I don’t love either one. I guess I will go with the American cover, because it’s a smidge less generic? I don’t know. I don’t feel happy about it.

The end (spoilers in this section only, so skip it if you don’t want to know): This is not my first rodeo. Good outcomes are unlikely in books about sharecropping and racism in 1946 Mississippi. Duly, the end of the book indicates that the the Jacksons have packed up everything to leave the town, following some kind of racism-related violent thing that has befallen their oldest son. It also appears that Jamie killed his father. I paged backward to find out why and really really wish I had not, because the murder motive is tied to what happened to the Jacksons’ son, and it’s much horrible than I was imagining. If I had not been reading this book for book club, I’m not sure I’d have finished it. I do not have the stomach for this kind of ugliness.

The whole: Mea culpa, friends. I couldn’t finish this book, even though it was a book for work book club. The ending was brutal, and when I got far enough into the book to observe that it was going to be brutal all the way through, and culminate with the horrible thing I read about at the end, I just couldn’t take it. This:

[Ronsel, a black World War II veteran] tried to step around them, but Orris moved to stand in his way. “Well, looky here. A jig in uniform.”

Ronsel’s body went very still, and his eyes locked with Orris’s. But then he dropped his gaze and said, “Sorry, suh. I wasn’t paying attention.”

Y’all, I don’t know, it has been a rough month and maybe I am emotionally fragile, but when Henry McAllan went to the Jackson’s house later, and made Ronsel apologize to the men who called him “boy” after he fought for his country, and made him leave the store through the back door, I don’t know. I couldn’t handle it.