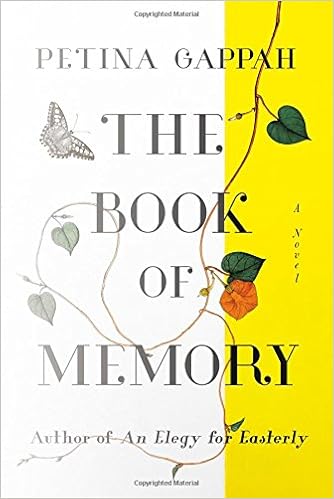

Remember before, when I was reading Anthony Schneider’s Repercussions and talking all about how I wished I read more books about good people who are trying their best? Guess what happened! I read The Book of Memory, which is about an albino woman in Zimbabwe who’s in jail for murdering the white man to whom her parents sold her when she was nine years old. Guess what it is about! Contrary to expectation, it’s totally about good people trying their best!

I know, I know, I know what you are thinking. You’re thinking: But, murder? But, selling a child to an adult man? I perfectly understand your concerns. Nevertheless, and trust me, The Book of Memory is all about good people trying their best. I was interested in this premise before I began reading, but the book surprised and moved me with where it took the story of Memory’s past and present. This is a story about things not being what they look like, and that is a type of story I absolutely cherish.

To begin with, of course, there’s Memory herself. As an albino child in her home township of Mufakose, she is accustomed to drawing the confused (at best) and hostile (at worst) glances of those who see her. She’s a freak, an oddity, an exception in her own family, perhaps a witch or evildoer, simply because of the color (lack of color) of her skin and hair. Under Lloyd’s care, she’s seen as a servant, a ward, a charity case. At the same time, although Memory herself is rarely seen for who she really is, it doesn’t make her any better at seeing the world around her clearly. Like the judges on her case, like the people of her township, like us as readers even, Memory’s vision is clouded by what she expects the world to look like.

The Book of Memory is Petina Gappah’s first novel, and it bears some of the marks of a first novel. Certain plot threads are underdeveloped, such as Memory’s doomed relationship with an artist called Zenzo, and it’s possible too much is made early on of the murdery-mystery bits of the book, considering that Lloyd’s death isn’t really the point of the book. But Gappah’s writing is wry and readable, and I fell in love with even the most minor of her characters.

Some bits I liked:

His career has risen with our country’s collapse. . . . His painting speaks truths that the government wants to hide, it is said. He is the artist exiled from his homeland because his work shows a reality before which the government flinches. None of it is true, but who cares for truth when there is a troubled homeland and tortured artists to flee from it?

It will not be possible for me to escape the past. But if I go back there, it will only be to find ways to make rich my present. To accept that there are no villains in my life, just broken people, trying to heal, stumbling in darkness and breaking each other, to find a way to forgive my father and mother, to forgive Lloyd, to find a path to my own forgiveness.