I recently began reading fairy tales to my little nephew, on the grounds that everyone should know fairy tales and he hasn’t really experienced them before. He was either into it or giving a good impression of being into it because he’s very into me: We read “Snow White” first and then he picked out “Rumpelstiltskin” and “The Frog Prince” from my book, and on another day he asked me for a story and I told him “Rapunzel.” It should be noted that there are no positive messages in any of these stories. The couple in “Rumpelstiltskin” allegedly live happily ever after even though he imprisoned her for days at a time to get her to do an impossible task.1 At least the witch who imprisons Rapunzel is understood to be wicked. If she’d been a handsome prince who did that, they’d definitely have gotten married in the end. Yet here I go, telling the stories to my little nephew, planting the weeds of kyriarchy in his defenseless baby mind.

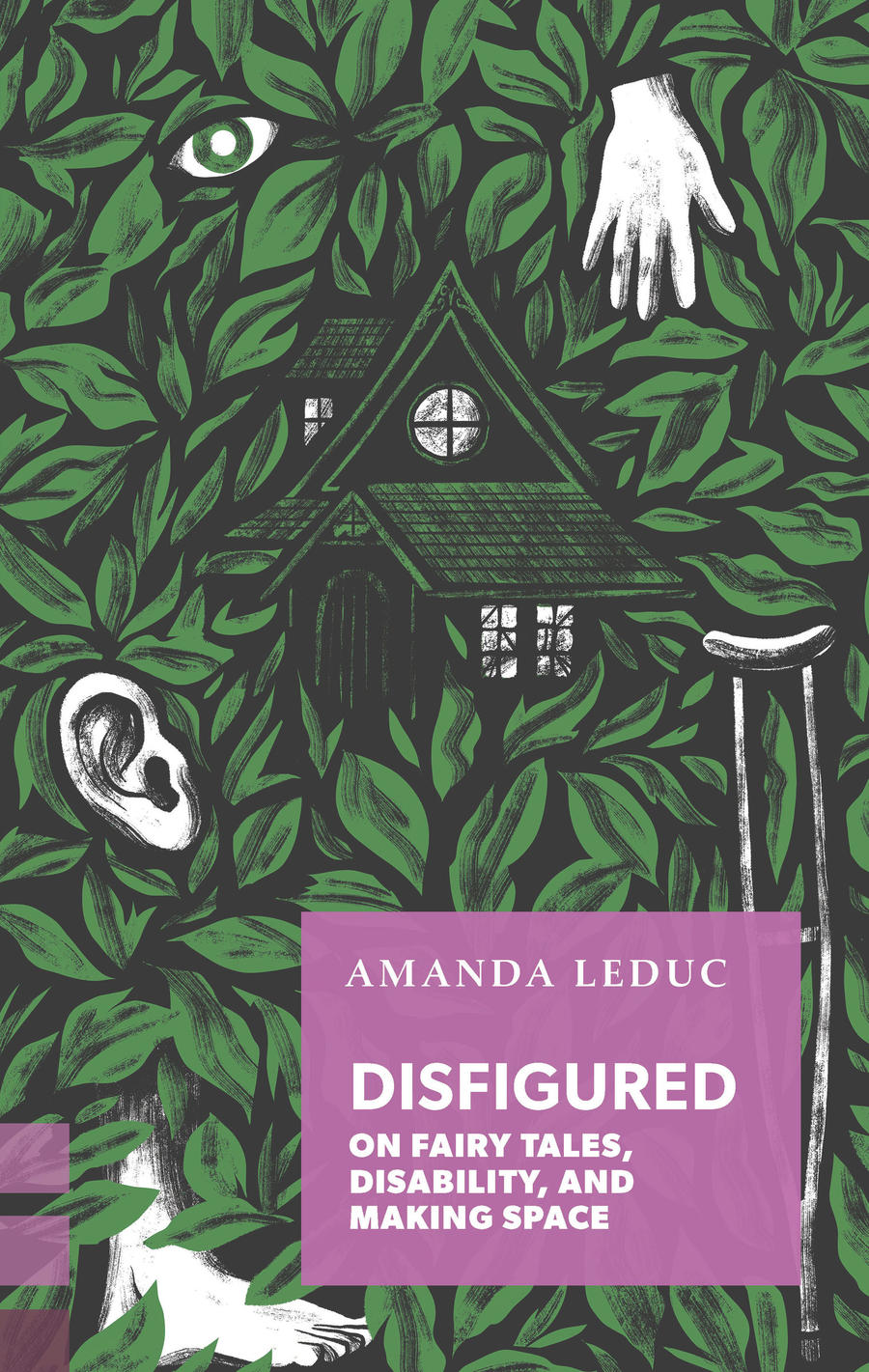

As a child, Amanda Leduc loved fairy tales (like me!). As a child, she was diagnosed with and treated for cerebral palsy and spastic hemiplegia. Disfigured is her attempt to understand why fairy tales are so fascinated by disability and why, at the same time, they so consistently deny the personhood and morals of any disabled character. Leduc blends her analysis of fairy tales with exploration of the personal experience of disability, drawing on interviews with other disabled writers as well as notes and memories of her own treatment as a child and into adulthood.

Leduc notes that fairy tales comprise some of our oldest and most enduring stories, retold over and over down the generations. The protagonists are models of beauty and grace, with a few rare exceptions — and in the case of those exceptions, Leduc notes, the protagonist must always be the one to change. The world will never change to accommodate them. She gives the example of the story “Hans My Hedgehog,” the protagonist of which is half hedgehog (waist up) and half man (waist down), because, sure. Hans advocates for himself, makes a life for himself, and his reward at the end is to be transformed into a complete man. “In fairy tales,” Leduc writes, “the transformation of the individual relies on fairies and magic — or the gods — because it’s understood that society can’t (and indeed won’t) improve.”

By the same token, the longing to fit in pervades fairy tales, not just among the disabled characters, but for everyone. And they offer a model for how to fit in! All you have to do is be normal. Yes, sometimes you can achieve belonging by being just and true for long enough that somebody notices and swoops you away from the meanies you live with. But even if that does happen, your happy ending depends exactly on your conformation with a set of bodily and social standards. You must be normal! Here’s how: You must desire marriage, especially if a girl. You must attain prosperity. You must be good-looking, a category that inevitably encompasses able-bodied-ness. If you fail on any front of this prescription to normalcy, no happy ending for you.

Moreover, moral lapses in disabled fairy tale characters are often part and parcel of their disability. The skinny, scarred lion is the wicked one. The Beast is cursed with monstrosity because of his bad behavior. The implication is that inner beauty is reflected in appearances, and disabled people are a) unbeautiful and b) externally unbeautiful because they are internally unbeautiful too. Even when a wicked character is beautiful, the fairy tales often highlight the disparity: Though she was beautiful, her heart was hard and ugly. Like, can you believe it? Someone hot, but mean? Meanwhile a beautiful protagonist may lapse in her morals but will not be physically marked by it. Her beauty is proof of her baseline goodness.

All of this is deeply personal, and Leduc makes it personal. “Fairy tales and fables are never only stories: they are the scaffolding by which we understand crucial things.” As a little girl whose doctors and parents were working hard to identify her disability and find suitable treatments to keep her healthy, Leduc wanted to be a princess like the ones in her stories. But though she craved their happy endings, she never saw herself reflected in their bodies and lives. Fairy tales and other stories tell us which kinds of bodies are valued, and which are disposable.

I started writing this review before coronavirus really hit hard, and then got distracted. Since then, there has been a lot more talk about which lives to save, in a time of crisis, and it’s reminded me of just how important work like Leduc’s is in countering societal narratives about the worth of disabled lives. I highly recommend this piece by Alice Wong, as well as her work more generally and the work of SE Smith, Vilissa Thompson, Rebecca Cokley, and Sara Luterman.

- This was also why I didn’t ultimately love Spinning Silver, because it turns out you just can’t make that premise okay. ↩