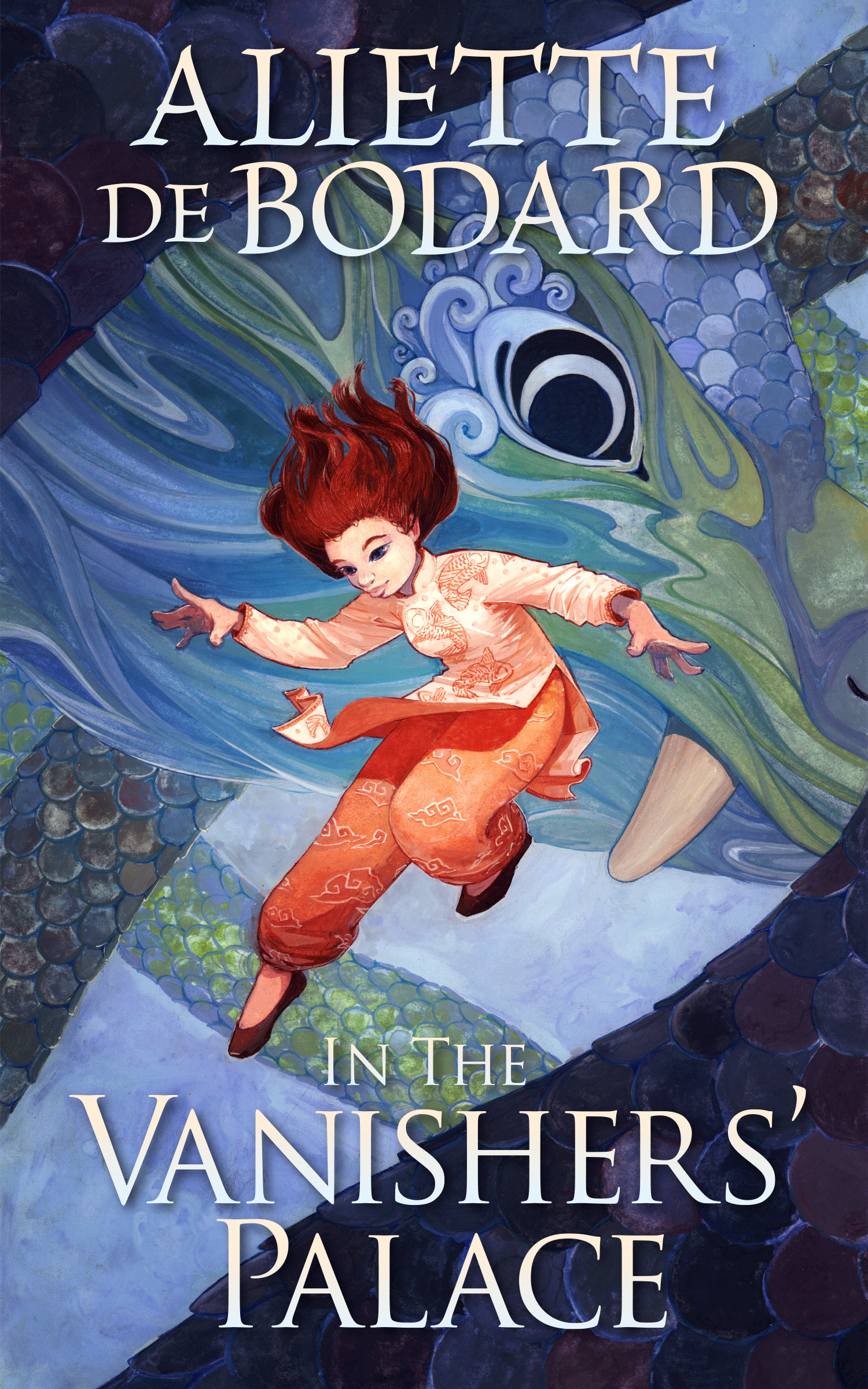

Friends, I am very, very choosy about my “Beauty and the Beast” retellings. To the best of my recollection, the only one that I have ever loved is Robin McKinley’s Beauty.1 I liked Uprooted, but I loved it best when it was doing things other than retelling “Beauty and the Beast.” I hear good things about W. R. Gingell’s Masque, but I am not pinning my hopes on it. So when I tell you that I was blown away by Aliette de Bodard’s novella In the Vanishers’ Palace, a queer retelling of “Beauty and the Beast,” I want you to understand that the bar was high, and In the Vanishers’ Palace easily cleared it.

Yên is living on borrowed time. After the world was poisoned by the Vanishers, who introduced viruses and gene mutations and ruined everything and then left, villages only keep people around if they’re useful, and Yên knows she isn’t. So it’s not much of a surprise when the village offers her to the shapeshifter dragon Vu Côn in payment of a healing Vu Côn has performed for them. When she gets to Vu Côn’s palace, she learns that she’s to be a tutor: Vu Côn is a mother, and doesn’t have the time to provide an adequate education to her twin teenagers. But the longer Yên stays at the palace, the more drawn she is to Vu Côn.

The device of the Beast needing the Beauty for something specific is a brilliant one. So often in these retellings, the Beauty character has nothing much to do except wander around the palace poking her nose into things and getting into trouble. Here, Yên immediately has a task, and Aliette de Bodard won my heart completely with these two kids. The truism about teenagers is that they’re sulky, uncompliant, and irresponsible. Thông and Liên are definitely finding ways to separate themselves from their mother, as teenagers do, — especially Thông — but they both care deeply about being good people and doing the right thing. It’s a major subplot in the book! How to raise children into good people; how to be a good person despite one’s worst instincts. In these troubled times, but also always, these are themes that resonate with me very strongly.

The bigger pitfall in “Beauty and the Beast” stories is, of course, consent. Fairy tales have a dreamy, unspecified quality that makes it possible for them to get away with leaving a lot of things unexplained. Retellings don’t have that luxury, and it’s rare for me to feel happy with the way an author manages the question of whether Beauty, a lifelong prisoner, can meaningfully consent to a relationship with her captor. In the Vanishers’ Palace cares deeply about this question, and the broader corollary of what it looks like to be the more powerful one in a relationship. What can we decide for the ones we love? What should we? Vu Côn grapples with this throughout the book, and I love where she ends up.

An atmospheric gem of a retelling. Do yourself a favor and pick up a copy when it comes out tomorrow.

PS: In the language of the book, “I” pronouns are gendered, so that when a person says “I” you immediately know what pronouns to use for them. What a great idea! Is English working on this? Gendered first-person neopronouns? Can we have those?

PPS: I received an e-ARC of this book for review consideration.

- And the Disney cartoon! That’s a movie, though. ↩